(aka,

The Crucified Lovers)

One of the bonus features of my (beautiful)

Chikamatsu Monogatari DVD is a short discussion with Mizoguchi 'expert' Tony Rayns. It's an informative piece rather than an analytical one, and he claims that the film is lesser Mizoguchi, suggesting that the director wasn't entirely committed to the film - in part, due to the messy end to his professional (and personal?) relationship with favoured actress, Kinuyo Tanaka. His points aren't lost on the viewer, but although

Chikamatsu isn't as supreme an artistic achievement as

Sansho the Bailiff (one of the five greatest films ever made, for those who continue to live in ignorance) or even

Ugetsu, it's nevertheless a fantastic demonstration of Mizoguchi's ability to elevate mediocre material simply with the sophistication of his craft.

It's not difficult to grasp why the director would be suited to this story. Thematically,

Chikamatsu is typical Mizoguchi thanks to its concern with the oppression of females, the rigidity of social hierarchies, the hypocrisy of patriarchal conventions etc. etc. Unusually for Mizoguchi however, the narrative that gives birth to these ideas is only partially successful. The central romantic drama rests upon contrivances that require a wilful blind-eye on the audience's part, and its melodramatic nature is convoluted by the decision to expand the scope by interweaving underdeveloped subplots concerning the Master and Otama (a servant in love with Mohei, the male lead.)

Chikamatsu's characters are further hindered by a horrid tendency to expose concerns that the narrative and/or Mizoguchi already makes clear - thus, after a premonitory crucifixion procession we're browbeaten with the Master's unnecessary articulation of the consequences of adultery, which is followed by a group of female servants questioning the misogynism inherent within the prevailing status system. It's startingly uncharacteristic of Mizoguchi to treat his audience with such disrespect, so one could be forgiven for wondering whether Rayns's arguments about the director's engagement with the production are legitimate.

Well, actually - no! One couldn't and

shouldn't be forgiven for doubting the credentials of the greatest of all the Japanese

auteurs (I'm calling it.) How easy it is to forget that this is the same director who ironed out the creases in

Ugetsu's problematic screenplay with his unrestrained lyricism, thereby deeming it worthy of the 'masterpiece' moniker.

Chikamatsu lacks the stylistic flourishes that makes

Ugetsu (and also

Sansho) such captivating viewing, but it

does reveal a refinement in Mizoguchi's technique that's advantageous in terms of taming the melodrama. Above all, the film is an exercise in elegant

restraint - each composition quietly ripens the subtext, achingly edging the audience closer towards its moving culmination. The overriding motivation behind much of Mizoguchi's framing is the issue of entrapment:

Chikamatsu is overtly concerned with the concept of freedom, so it follows that for much of the film's first half (when the would-be lovers exist

within the social order) the drama is interiorized into the cluttered spaces of the Master's house. Mizoguchi frequently uses this

mise-en-scène as a 'device' to confine his characters even further within the already-tight frames, or to emphasize the distinctions between the public and private spheres of the household. In reality, this 'device' discloses the spuriousness of their confinement and the tragedy of self-imprisonment: all that binds these characters to their mores is a series of

man-made constructs.

Chikamatsu Monogatari is not simply another sentimentalized paean to the resilience of the human spirit, however. Mizoguchi's use of repetition as a cinematic accessory fortifies the depths to which this legacy of entrapment has been ingrained into the society of this era: the film uses exactly the same establishing shot of a busy street during the opening in Kyoto (the home of the "crucified lovers", therefore associated with their confinement) as it does upon the lovers' escape to Osaka (which, briefly, becomes associated with their freedom.) 'Civilized' spaces refuse to grant the couple a reprieve, so only in the organic settings of countryside, lakes and forests can intimacy occur.

Chikamatsu deals with a love that's stifled, so its rare emergence implores us to treasure its value all the more. Additionally, the drama that accompanies these moments of romance is nigh-on unbearable due to the consistency in Mizoguchi's subdued treatment of the story that surrounds it. Nevertheless, even in the elegiac beauty of the natural world, the pair are constantly forced into enclosure (a peasant's hut, a makeshift treehouse, Mohei's familial home) - the reality of the bloodthirsty world they inhabit catches up with them at each and every turn.

[SPOILERS HEREIN]Tragically then, we come to the realization that the only avenue which presents an escape into the spiritual freedom that our protagonists' crave is that of death. Cruelty, greed and selfishness are the traits which taint the personalities of nearly

all of the film's notable characters. Even those that we initially trust, such as Osan's mother, are eventually unmasked as merely another facet of this incriminating portrait. What these characters have in common is their conformity - they live by the status quo (although the ease with which Mohei, Osan and eventually the Master lose their place in their hierarchy reveals a wicked paradox between the rigidity of the order and the precariousness of the social status that it provides.)

Chikamatsu doesn't suggest that obliterating the rulebook is the path to guaranteed enlightenment, but it does ask its audience to consider the restrictions of the world in which they exist and then presents an outlet for countering those limits: love. The beauty of this particular prescription is the surprise with which that love confronts its recipients, privileging them - however briefly and inadvertently - with a taste for

living, as voiced by Osan herself after an aborted suicide attempt. It's this that lends

Chikamatsu's finale its poignant intricacy. Mizoguchi's repetitional device resurfaces here, with a second crucifixion procession that augments the cyclical nature of his filmic world. The sequence is harrowing, explicitly recalling its predecessor and provoking a replacement of the first procession's anonymity with sorrow as we're forced to comprehend the fact that our "crucified lovers" are not the only ones. The gravity of this implication is contrasted with the serenity of the lovers' faces - both are calm, at peace. For the first time in their lives, they are genuinely

free. And yet, the deplorable cost of this freedom is not lost on Mizoguchi, who leaves it up to an innocent bystander to articulate the express the bitter irony of the situation: "It's hard to imagine that they're on their way to die." After the experience of

Chikamatsu Monogatari, one realizes that no, it's not hard at all - it's devastating.

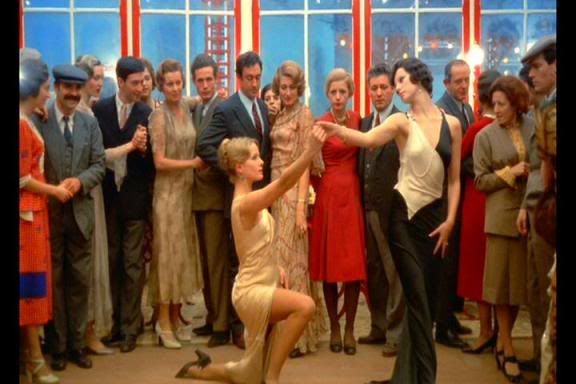

Thanks to the wonderful folks over at Masters of Cinema, the Chikamatsu DVD features another Mizoguchi from the same year: Uwasa no onna (aka The Woman in the Rumour.) It's a relatively short effort (84 mins) so I decided to put some spare time this afternoon to good use by giving it a spin. This was my first experience with a contemporary film from the director, so I wasn't quite sure what to expect. Of course, the concern with women (specifically, prostitutes) is typical of Mizoguchi and to his credit, he doesn't shove the issue of their oppression down our throats. On the contrary, he spends some time articulating the possible empowerment and safety that the profession can provide whilst never losing sight of the instabilities that plague this world. Mizoguchi's knack for social commentary is at it's most effortless during these scenes in the geisha house. However, his astute observations share an uneasy relationship with the romantic turmoils that gradually assume the film's spotlight - frankly, they're just not that interesting despite the unpredictable directions that they take (the ease with which Dr. Matoba accepted Hatsuko's money really surprised me!) Fortunately, Mizoguchi isn't focused on the melodramatic aspects so much as he's concerned with the clash between traditionality and modernity. The distinct use of costume in this film (geishas sporting classical Japanese dresses, other characters in Western attire) underscores the tensions which manifest themselves most clearly in the mother-daughter relationship at the film's core. These conflicts are deftly played out by both female leads, but Kinuyo Tanaka's work as the ageing madame is particularly worthy of commendation. The actress lets loose here, using every fibre of her frame to convey her character's insecurities. It's a brave and highly expressive performance, which dares to use body language as a method for audience communication, and Tanaka pulls it off with ease. Her trademark ability to internalize her characters' anxieties is not lost either - the film's most memorable sequence occurs at a noh theatre where the cruelty of a comedy ridiculing an older woman's love becomes unbearable to watch thanks to Tanaka's heartbreaking reaction shots.

Thanks to the wonderful folks over at Masters of Cinema, the Chikamatsu DVD features another Mizoguchi from the same year: Uwasa no onna (aka The Woman in the Rumour.) It's a relatively short effort (84 mins) so I decided to put some spare time this afternoon to good use by giving it a spin. This was my first experience with a contemporary film from the director, so I wasn't quite sure what to expect. Of course, the concern with women (specifically, prostitutes) is typical of Mizoguchi and to his credit, he doesn't shove the issue of their oppression down our throats. On the contrary, he spends some time articulating the possible empowerment and safety that the profession can provide whilst never losing sight of the instabilities that plague this world. Mizoguchi's knack for social commentary is at it's most effortless during these scenes in the geisha house. However, his astute observations share an uneasy relationship with the romantic turmoils that gradually assume the film's spotlight - frankly, they're just not that interesting despite the unpredictable directions that they take (the ease with which Dr. Matoba accepted Hatsuko's money really surprised me!) Fortunately, Mizoguchi isn't focused on the melodramatic aspects so much as he's concerned with the clash between traditionality and modernity. The distinct use of costume in this film (geishas sporting classical Japanese dresses, other characters in Western attire) underscores the tensions which manifest themselves most clearly in the mother-daughter relationship at the film's core. These conflicts are deftly played out by both female leads, but Kinuyo Tanaka's work as the ageing madame is particularly worthy of commendation. The actress lets loose here, using every fibre of her frame to convey her character's insecurities. It's a brave and highly expressive performance, which dares to use body language as a method for audience communication, and Tanaka pulls it off with ease. Her trademark ability to internalize her characters' anxieties is not lost either - the film's most memorable sequence occurs at a noh theatre where the cruelty of a comedy ridiculing an older woman's love becomes unbearable to watch thanks to Tanaka's heartbreaking reaction shots.