Bigger Than Life professes to tell the story of a "miracle drug" (cortisone) and the adverse reactions that it provokes in an unsuspecting schoolteacher and his picture-perfect family. This isn't simply a cautionary tale about the potential perils of drug usage, however - Ray's scope broadens to attack the very idea of placing blind faith in such unproven solutions. Moreover, whilst watching the film one realises that the role of drugs in its thematics is surprisingly minimal: the most pertinent concern lies with the "American Dream" and the fragility of that concept. The director's meticulous attention to detail deftly subverts this paradigm until it's exposed as little more than a fraudulent and unattainable fantasy - and rarely has the dissolution of an ideal made for such absorbing viewing.

Bigger Than Life professes to tell the story of a "miracle drug" (cortisone) and the adverse reactions that it provokes in an unsuspecting schoolteacher and his picture-perfect family. This isn't simply a cautionary tale about the potential perils of drug usage, however - Ray's scope broadens to attack the very idea of placing blind faith in such unproven solutions. Moreover, whilst watching the film one realises that the role of drugs in its thematics is surprisingly minimal: the most pertinent concern lies with the "American Dream" and the fragility of that concept. The director's meticulous attention to detail deftly subverts this paradigm until it's exposed as little more than a fraudulent and unattainable fantasy - and rarely has the dissolution of an ideal made for such absorbing viewing.From the outset, any illusions of a middle-class utopia are quickly undermined. The personal life of Ed Avery (James Mason, providing one of the extraordinary screen performances) forms a diametrical opposition to the petit bourgeois impeccability that his household radiates in more public environments. Ed is discontent: he feels undervalued as a schoolteacher (reflected by his poor salary), and accordingly feels compelled to take on an 'inferior' part-time job at a garage; he's amiable, but cares little for the soirées that his social status deems a necessity (he sits out most of an early bridge game); he's awkward with his son, dispassionate with his wife, and at one point he flat-out states that "we're dull!" when referring to his family. Ray's mastery means that the very slightest of details can further contribute to these early assessments of Ed's predicament: like the quaint bow-tie that he wears, signifying his perceived superiority over his colleagues; or even Mason's distinctive English accent, which works at odds with the self-image of an all-American high school football hero that he memorializes (and later, attempts to project onto his son), and effectively underlines the fallacies inherent in his lifestyle.

Having established this façade then, the film introduces its "miracle drug" - whose negative side-effects are not isolated from these initial dramas. The cortisone functions here as a catalyst for Ed, unleashing the insecurities that already exist within him, thereby weaving a megalomaniac from the fabric of his own personality. "Bizarre" is perhaps the only word one can use to describe a film audacious enough to equate the addictive pursuit of the American Dream with a dependence on prescription drugs, but Ray somehow pulls the conceit off with aplomb. Ed's increasing paranoia allows Ray to create a scathing indictment of middle America, damning the conformity of his characters whilst manipulating the sudden realisation of their goals in order to unnerve them back into conventionality. It should be noted that Ed is not the only character who slides into mental turmoil - his wife Lou's complete regression into the role of submissive absorbent of Ed's verbal abuse ("Why couldn't I have married my intellectual equal?") is equally delusional, as is her misplaced blind faith in the power of love. What eventually emerges is a despondent portrait of bourgeois life in which Ray brutally unmasks a crisis of self-entrapment - for which he provides no route for escape.

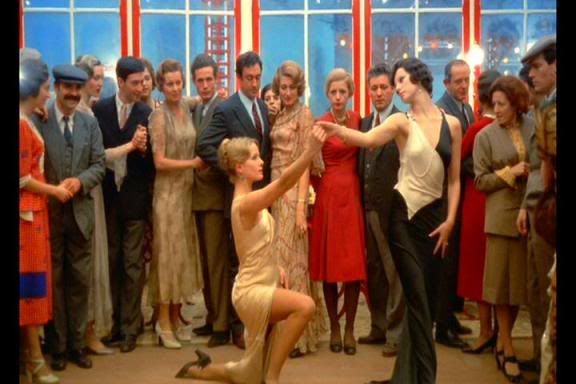

It's difficult to imagine there being more conclusive justification for Nicholas Ray's place in the canon than his achievement here (and should such justification exist, then he needs to be propelled into the upper echelons of that pantheon immediately.) The nature of Ray's material requires him to indulge the melodramatic aspects of the story, so his sets are appropriately bold whilst remaining infinitely rewarding. His use of colour is especially noteworthy - dull, lifeless hues dominate the palette for the early scenes (bar the odd splash of ominous reds) but a revelatory 'makeover' sequence in a fashion store (which Hitchcock surely ripped off for Vertigo) sees the addition of much brighter shades that highlight the growing disconnect between Ed's reality and the socio-economic ambitions that ultimately prove beyond him. These ambitions are reinforced in the familial home - that paradise of domesticity which Ray perturbingly reconceives as a suffocating nether-world of blandness - where a series of posters depicting various European cities prominently adorn the Averys' walls. Indeed, one of the most brilliant compositions in the film sees Ed and Lou at opposite ends of the widescreen vista, with a map of the world engulfing the space between them. The director's dexterity over his mise-en-scène doesn't end there, however - to borrow just a few of the more memorable examples: a staircase is transformed into a metaphor for Ed's mental state; a cracked mirror temporarily shatters his unruly ego; and most chillingly, a manipulation of light sources allows his menacing shadow to fulfil the film's titular promise during a scene of intellectual and emotional torture. Throughout the film, Ray constantly searches for ways to further articulate and augment his narrative's psychological complexities, culminating in a harrowing finale to Ed's mental traumas where he assumes the role of a Bible-thumping charlatan and spits out the film's most immortal line: "GOD WAS WRONG!" Both visually and aurally, the madness hits a peak here with the grotesque excesses of materialism crashing with a thud as a mocking soundtrack emanates from the television (that most iconic of consumerist symbols) in the background.

Bigger Than Life is essentially a cinematic treatment of those all-too familiar Hollywood themes: the American dream, suburban life, the hollowness that resides within etc. etc. And yet, despite being a fifty-year-old melodrama, it miraculously seems to have retained every ounce of its potency over the years - in fact, I'd go so far as to say that it's the definitive film on those aforementioned themes, by quite some distance. Aside from Nicholas Ray's previously-noted talents, one could argue that the film's outright success can in part be attributed to the way in which it uses its core social concerns as a platform from which to explore other ideas. Thus, the issue of schoolteachers' paychecks assumes relevance (one could argue that it's economic demands that disrupt and then drive Ed's state of mind) alongside the limitations of medical science, and during the final act the film takes on a quasi-religious dimension with Ed's numerous biblical references. One could even go so far as to draw parallels between the latter stages of Ed's illness, and the (supposed) totalitarians of history. Does the film attempt to implicate those "bigger than life" figures alongside Ed Avery? Such theories are perhaps far-fetched, but the fact that the text allows for even their consideration speaks volumes about the respect with which Ray gifts his audience, not to mention the thought-provoking substance of his art. Another facet of the film's genius is its sly sense of humour: the external world (the school, the hospital, the pharmacy, the milkman) frequently provides a source of comic relief for the audience that's notably lacking in the internal environments of the Avery household, allowing the film to briefly flirt with the territory of entertainment.

Of course, perhaps the most fundamental point to make about Bigger Than Life's success is the most obvious one: it's a superb character study that penetrates extraordinary depths during its relatively short length. One cannot emphasise the greatness of James Mason's work here enough, his ability to sell a role with so much room for failure is a triumph far beyond the descriptions that mere words can provide. As for the character that he sells - Ed Avery is a man whose not a victim of insanity so much as he is of his own repression. What's so striking about this portrayal is how ordinary it is. Take the notorious parents' evening scene at the school: it's not so much the philosophy that Ed spouts during his diatribe that's a cause for contention (some of the parents in this scene agree with him, and the idea that children are born bad and must be socialized into goodness is not one without its believers), but the spite with which he espouses it: "childhood is a congenital disease, and the task of education is to cure it!" Furthermore, Ed's initial scenes after consuming the cortisone can just as easily be described as "enthusiastic" and "passionate" as they can "volatile" and "unhinged." The unease which this film induces is a result of Ray's decision to make Ed an utterly average human being with a completely tangible lifestyle - in short, he comes to represent the everyman: aka, the target audience itself. As a result, the film's overwhemlingly pessimistic worldview combines with the precariousness of Ed's social acceptability to create a critique that's conclusively damning of us. Ray provokes us to reconsider the security of our own lives, and orders us to examine whether our private worlds are capable of spinning violently out of control should a "miracle" occur. That a mere film could render such outlandish situations completely plausible is what makes Bigger Than Life - and not cortisone - the bitterest of all pills to swallow.

A few quick notes on the ending, which requires HEAVY spoiler alerts:

[Spoiler:] If people perceive the ending of this film to be a "happy" one that diminishes the rest of the film (and, judging by the film's inexplicably low IMDb rating, I'm going to presume that they do) then allow me to vehemently disagree. To see light here is to remain blissfully ignorant of what Ray has spent the previous 90 minutes telling us: which is that Ed's 'madness', his arrogance, his snobbery and his prejudices were already within him as an individual prior to the cortisone. Despite the doctors' insistence for him to "learn" from his experience at film's end, there's nothing substantial enough to suggest that he will have done so. By hugging Lou and Richie, he is entering back into the problematic social repression that we witnessed during the first part of the film. In essence: he will be living a lie. Moreover, the experience that his friends and family have shared with him, and the horrid depths to which he sank are hardly memories that are going to be easily erased in these characters' mindsets. Of particular importance here is the role of Richie, where one recalls the ghastly confrontation at dinner over the milk pitcher as Ray's camera slowly tracks forward - erasing both Ed and Lou from the frame and focusing solely on the effects of this breakdown upon Richie himself. As anyone should well be aware, childhood traumas leave a colossal impression, and what Richie has experienced (his dad attempting to murder him) is no doubt going to shape his development more than any of Ed's mathematical inquisitions ever could. Finally, I suggested earlier that it was the economic demands that were driving Ed's recklessness - well, we conclude with no resolution to his financial woes. If anything, he is in a weaker position than before. So I repeat: do not be fooled by the Hollywood machine here, Ray's subversions deserve far closer inspection.